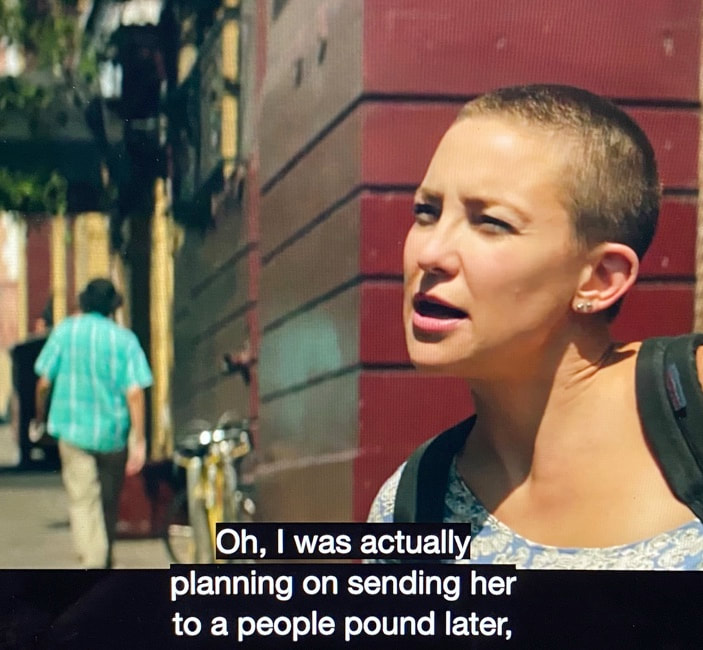

I watched Sia's Music so you don't have to The night that Sia’s debut film Music was released in the United States, I watched it on my computer screen. Not because I’m a fan, or because I was excited to see representation of an autistic person in film. I rented the movie because I didn’t want anyone else to feel like they had to watch it. I am autistic. I was diagnosed between the ages of 8 and 9, after years of severe meltdowns, social struggles, and sensory issues that left my parents (and myself) confused and desperate for answers. Now, a decade later, I run a self-advocacy platform on social media called The Autisticats with several of my autistic friends. I’ve been following the situation with Sia’s film from the day she released the trailer, back in November. And as the whole fiasco has developed, I’ve been writing a series of posts for The Autisticats about the issue. People in the comments section and in DMs ask me lots of questions about those posts, but one that I receive the most frequently is: “How can you say this about the film if you haven’t even watched it yet?” So I knew, ultimately, that I would have to- no matter how much it hurt. Going into it, I was aware that the movie would be bad. I knew it would make me feel uncomfortable in my own skin, and I knew that I would probably get overstimulated. But I still wasn’t prepared for what I saw. As it turns out, Music is a perfect example of Murphy’s Law: everything that can go wrong, will go wrong. The opening scene of the movie made my stomach drop. It begins with Maddie Ziegler (as the nonspeaking autistic character, Music) in a pair of white underwear, dressing herself. She grunts and moans, and starts hitting her legs after putting a pair of white pants on (this struck me as an unusually intimate way to begin a film of this nature, and it was uncomfortable to watch because Ziegler isn't actually autistic). Every single item of clothing Music wears, throughout the whole movie, is white. I assume that this costume choice is meant to symbolize innocence and purity- an ableist trope often employed in stories about developmentally disabled people. Right after watching Ziegler dress herself while mimicking autistic body language, the viewer is launched into what I can only describe as a total sensory nightmare. The first dance sequence of the movie, in which Music wears braids shaped like headphones and another white child actor is seen in Bantu knots, is full of aggressive warm colors and rapidly flashing lights (which could easily cause seizures in viewers with photosensitive epilepsy). One minute into this movie, and I was already overstimulated. Yet somehow, the sensory overload wasn’t even the worst part of my experience during this first scene. What hurt the most was watching Ziegler’s grotesque, robotic impersonation of autistic movement and body language. When I was younger, I would roll my eyes and put my front teeth over my bottom lip as a stim. I still flap my hands, flick my fingers, rock, and do just about every other “classic” stim you can think of. But I don’t stim as much in public anymore, because of how those mannerisms have been received. One time when I was in a gymnastics class at around six or seven years old, I was rolling my eyes really hard while facing my teacher, who was across the room. She called my name, and said “Don’t roll your eyes at me!” I told her I wasn’t, but she replied with “I know what I saw,” and then told me to sit out of the next activity. There was nothing I could do to make her believe me; to believe that I was stimming, not being disrespectful. So to see a neurotypical actress portray an inorganic, stereotypical version of the same stims I was shamed and misunderstood for as a child, knowing that she has never faced the same stigma or internal distress from trying to suppress natural movements, gutted me. Zielger doesn’t know how to stim like I do, and the fact that she was forced to try (even though she cried during filming because of it) is unacceptable. There is almost no way to accurately direct a non-autistic person to move like an autistic person, because the way we move is so deeply entangled with our neurology. And yet, as I kept watching, it became apparent to me that I would have to endure this open-mouthed caricature until the end credits. Thanks, Sia. After the first dance scene, I watched Music get ready for the day. Upon waking up she brushes her own teeth, dresses herself, puts on her shoes, etc. with no external help. Then she walks down a busy city street and is greeted by all sorts of incredibly friendly people before arriving at the library, where she begins reading a very dense book about dogs. Several questions formed in my mind while watching this, which crystallized after finishing the film: Since Music is clearly able to read and comprehend language at a high level, why doesn’t she have a robust AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) system to communicate complex thoughts and feelings? Why does the film confine her to existence as a one-dimensional prop who cannot think for herself? The only phrases on her AAC device are pre-programmed, simple sentences including “I am happy” and “I am sad,” and the only glimpses we get into Music’s supposed “inner world” are nauseating dance sequences that feel like bad acid trips more than anything else. Viewers are not granted the opportunity to truly understand Music’s perspective, because her autonomy is stripped away. Nothing distilled this point more for me than a series of scenes in which Zu, Music’s half-sister who is also a recovering drug addict, attempts to institutionalize her. On the night that she’s given custody of her sister, Zu calls the LA Department of Mental Health and asks, “Do you guys do pick up? Like, if I got a kid that needs to be picked up? Or do I have to come in and drop her off?” The woman on the other end of the line replies, “Like a laundry service?” and Zu makes a facial gesture that can be summed up by the phrase: yeah, pretty much. The next day, when talking to their neighbor Ebo (the only African character in the movie, who is also the only character with HIV/AIDS), Zu says, “I was actually planning on sending [Music] to a people pound later, but I guess I’ll keep her a little longer.” (Zu telling Ebo that she plans to institutionalize Music) People pound. A short phrase that has been pinned to the forefront of my consciousness ever since watching this scene. So simple, so pointed, and so dehumanizing. Nonspeaking autistic people are not animals. Autistic people with high support needs are not animals. Intellectually and developmentally disabled people, across the board, are not animals. We are not dogs, or cats, or hamsters. Every last one of us is a human being who does not belong in an institution. Yet, at the end of the film, Zu nearly follows through. It is only when Music spontaneously says “Don’t go. Sit down now,” while sitting on the bare white bed in what could end up being her room for decades to come, that Zu rethinks her decision to commit her sister to a lifetime of seclusion. I ask again: Why does Music never get a say in her own future? Why does her only moment of self-advocacy occur after she has already arrived at the institution, in a way that is suspiciously convenient for Zu’s character development? If Music was her own character instead of being relegated to her position as a tool for the evolution of her caregivers, this would be an entirely different movie. But this is not that movie. It’s a movie where Music is held in prone restraint during meltdowns, despite the often fatal nature of that type of restraint (which I have experienced multiple times myself, and thankfully survived, albeit with a surplus of traumatic memories). It’s a movie directed by a woman who has called autistic people “bad actors” ; who refused to listen to suggestions and input from CommunicationFIRST, the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, and The Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint; and who ultimately did not remove the restraint scenes or add a warning about them at the beginning of the film, despite her promise to do so. Perhaps the reason why Sia was so unprepared for the backlash to this film, was because she completed it on the assumption that autistic people are incapable of advocating for ourselves or providing input on issues that affect us. This was her achilles heel, and it mired the project in ableism. But apparently, ableism was not enough for Sia. The list of racial offenses includes but is not limited to: white dancers and characters in Black hairstyles such as Bantu knots (Ziegler included- she wears box braids in two dance scenes); a Chinese immigrant abusing his wife and murdering his son (hate crimes against Asian Americans are surging right now and this scene certainly didn’t help with the stigma that the community is facing); a scene in which Ebo- who, may I remind you, is the only character with HIV- tells Zu that his autistic brother is dead and that the people in his village considered autism to be a curse; Zu’s drug dealer (who appears to be white?) with his hair in cornrows while wearing various appropriated Asian clothes; a scene where Zu refers to a clay figurine as her spirit animal (Zu is not Native American and neither is Kate Hudson); and yet another bizarre dance scene in which Zu is wearing what appears to be an Asian dress, Music has on a headdress and clothing with a collar reminiscent of a qipao, and Music’s grandmother has literal chopsticks in her hair. Yikes. (Music’s white grandmother with chopsticks in her hair, wearing an article of clothing that is ambiguously East Asian but that, to my knowledge, doesn't fall directly in line with any actual style of dress in any modern East Asian culture) (Kate Hudson as Zu, wearing a dress that appears to be East Asian in origin) (Maddie Ziegler as Music, wearing a headdress and a dress with a collar that resembles a qipao. A fuller image of Zu’s dress can be seen in the background as well) I wouldn’t have even noticed the chopsticks in the grandmother’s hair if it wasn’t for my girlfriend Abby (who has mixed Korean and Japanese heritage), who watched most of the film with me and pointed it out as the scene ended. It was hard to take in everything that was going wrong, particularly because this dance sequence happened directly after the horrifying murder scene where a Chinese man kills his son after choking his wife. I still can’t figure out why Sia felt the need to include that scene, particularly since it’s not at all relevant to the plot. Then again, most things in this movie don’t make any sense. It feels like Sia tried to squeeze in every single offensive stereotype and instance of cultural appropriation that she could find. It makes me wonder how there wasn’t any substantial pushback from POC members of the cast or production team. It's likely that there was, but their concerns were ignored. It wouldn’t be the first time a white director has ignored critique on issues of race. But it’s a shame, because tragically poor decisions lie around every corner in this film, to such a degree that Abby and I had no choice but to laugh hysterically at them. The common thread that ties everything in Music together is this: Sia is trying to tell stories that aren’t hers to tell. She attempted to tell stories about autism, about Africa, about HIV/AIDS, about immigrants, and about domestic violence. Every single one of those attempts ended up reinforcing existing negative stereotypes. The only storyline she has credibility to tell is the one about addiction, and that is the strongest element of the film overall. If she had simply stuck to making a film about drug abuse without drawing in all of these other disparate groups of people, it would have been so much better for everyone involved. There are many other critiques of this movie out there, many of them written by nonspeaking or minimally speaking autistic people, which you should go read in addition to this one. Hari Srinivasan and Niko Boskovic have both written powerful reviews, and CommunicationFIRST has released a short film called Listen that everyone should watch as well. There was no way for me to cover every aspect of what went wrong here, or every single way that the film is out of step with reality. Another brief example that comes to mind is a scene at the very end of the movie where a service dog for Music randomly arrives in the mail, which is…. not how partnering with a service dog works (to say the very least). So many tiny details like this warrant further discussion, but I am unable to unpack all of them right here. So I just hope that, after reading this and however many other reviews you’ve already encountered, you will not give Sia any of your money by renting or purchasing this film. There are much better places to spend your money, and you can start with the three organizations I mentioned earlier in this piece: CommunicationFIRST, the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, and The Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint. All of these organizations need donations to continue the vital work they are doing. If you’ve made it all the way to the end of this piece, I want to thank you for taking the time to listen to my voice as an autistic person and survivor of prone restraint. There are so many other people in the community, particularly nonspeakers, who everyone should also be actively learning from. Sia failed to listen, but you can counteract her ignorance with education and understanding. - Eden If you would like to support me financially as I go through college and continue work for this account, you can donate to me via my Venmo (@ Eden-Summerlin) or my PayPal, paypal.me/EdenSummerlin.

21 Comments

|

AuthorsWe're the Autisticats: Eden, Leo, Laurel, and Abby. This is where we post our writing, musings about life, and other things we're working on. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed