I watched Sia's Music so you don't have to The night that Sia’s debut film Music was released in the United States, I watched it on my computer screen. Not because I’m a fan, or because I was excited to see representation of an autistic person in film. I rented the movie because I didn’t want anyone else to feel like they had to watch it. I am autistic. I was diagnosed between the ages of 8 and 9, after years of severe meltdowns, social struggles, and sensory issues that left my parents (and myself) confused and desperate for answers. Now, a decade later, I run a self-advocacy platform on social media called The Autisticats with several of my autistic friends. I’ve been following the situation with Sia’s film from the day she released the trailer, back in November. And as the whole fiasco has developed, I’ve been writing a series of posts for The Autisticats about the issue. People in the comments section and in DMs ask me lots of questions about those posts, but one that I receive the most frequently is: “How can you say this about the film if you haven’t even watched it yet?” So I knew, ultimately, that I would have to- no matter how much it hurt. Going into it, I was aware that the movie would be bad. I knew it would make me feel uncomfortable in my own skin, and I knew that I would probably get overstimulated. But I still wasn’t prepared for what I saw. As it turns out, Music is a perfect example of Murphy’s Law: everything that can go wrong, will go wrong. The opening scene of the movie made my stomach drop. It begins with Maddie Ziegler (as the nonspeaking autistic character, Music) in a pair of white underwear, dressing herself. She grunts and moans, and starts hitting her legs after putting a pair of white pants on (this struck me as an unusually intimate way to begin a film of this nature, and it was uncomfortable to watch because Ziegler isn't actually autistic). Every single item of clothing Music wears, throughout the whole movie, is white. I assume that this costume choice is meant to symbolize innocence and purity- an ableist trope often employed in stories about developmentally disabled people. Right after watching Ziegler dress herself while mimicking autistic body language, the viewer is launched into what I can only describe as a total sensory nightmare. The first dance sequence of the movie, in which Music wears braids shaped like headphones and another white child actor is seen in Bantu knots, is full of aggressive warm colors and rapidly flashing lights (which could easily cause seizures in viewers with photosensitive epilepsy). One minute into this movie, and I was already overstimulated. Yet somehow, the sensory overload wasn’t even the worst part of my experience during this first scene. What hurt the most was watching Ziegler’s grotesque, robotic impersonation of autistic movement and body language. When I was younger, I would roll my eyes and put my front teeth over my bottom lip as a stim. I still flap my hands, flick my fingers, rock, and do just about every other “classic” stim you can think of. But I don’t stim as much in public anymore, because of how those mannerisms have been received. One time when I was in a gymnastics class at around six or seven years old, I was rolling my eyes really hard while facing my teacher, who was across the room. She called my name, and said “Don’t roll your eyes at me!” I told her I wasn’t, but she replied with “I know what I saw,” and then told me to sit out of the next activity. There was nothing I could do to make her believe me; to believe that I was stimming, not being disrespectful. So to see a neurotypical actress portray an inorganic, stereotypical version of the same stims I was shamed and misunderstood for as a child, knowing that she has never faced the same stigma or internal distress from trying to suppress natural movements, gutted me. Zielger doesn’t know how to stim like I do, and the fact that she was forced to try (even though she cried during filming because of it) is unacceptable. There is almost no way to accurately direct a non-autistic person to move like an autistic person, because the way we move is so deeply entangled with our neurology. And yet, as I kept watching, it became apparent to me that I would have to endure this open-mouthed caricature until the end credits. Thanks, Sia. After the first dance scene, I watched Music get ready for the day. Upon waking up she brushes her own teeth, dresses herself, puts on her shoes, etc. with no external help. Then she walks down a busy city street and is greeted by all sorts of incredibly friendly people before arriving at the library, where she begins reading a very dense book about dogs. Several questions formed in my mind while watching this, which crystallized after finishing the film: Since Music is clearly able to read and comprehend language at a high level, why doesn’t she have a robust AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) system to communicate complex thoughts and feelings? Why does the film confine her to existence as a one-dimensional prop who cannot think for herself? The only phrases on her AAC device are pre-programmed, simple sentences including “I am happy” and “I am sad,” and the only glimpses we get into Music’s supposed “inner world” are nauseating dance sequences that feel like bad acid trips more than anything else. Viewers are not granted the opportunity to truly understand Music’s perspective, because her autonomy is stripped away. Nothing distilled this point more for me than a series of scenes in which Zu, Music’s half-sister who is also a recovering drug addict, attempts to institutionalize her. On the night that she’s given custody of her sister, Zu calls the LA Department of Mental Health and asks, “Do you guys do pick up? Like, if I got a kid that needs to be picked up? Or do I have to come in and drop her off?” The woman on the other end of the line replies, “Like a laundry service?” and Zu makes a facial gesture that can be summed up by the phrase: yeah, pretty much. The next day, when talking to their neighbor Ebo (the only African character in the movie, who is also the only character with HIV/AIDS), Zu says, “I was actually planning on sending [Music] to a people pound later, but I guess I’ll keep her a little longer.” (Zu telling Ebo that she plans to institutionalize Music) People pound. A short phrase that has been pinned to the forefront of my consciousness ever since watching this scene. So simple, so pointed, and so dehumanizing. Nonspeaking autistic people are not animals. Autistic people with high support needs are not animals. Intellectually and developmentally disabled people, across the board, are not animals. We are not dogs, or cats, or hamsters. Every last one of us is a human being who does not belong in an institution. Yet, at the end of the film, Zu nearly follows through. It is only when Music spontaneously says “Don’t go. Sit down now,” while sitting on the bare white bed in what could end up being her room for decades to come, that Zu rethinks her decision to commit her sister to a lifetime of seclusion. I ask again: Why does Music never get a say in her own future? Why does her only moment of self-advocacy occur after she has already arrived at the institution, in a way that is suspiciously convenient for Zu’s character development? If Music was her own character instead of being relegated to her position as a tool for the evolution of her caregivers, this would be an entirely different movie. But this is not that movie. It’s a movie where Music is held in prone restraint during meltdowns, despite the often fatal nature of that type of restraint (which I have experienced multiple times myself, and thankfully survived, albeit with a surplus of traumatic memories). It’s a movie directed by a woman who has called autistic people “bad actors” ; who refused to listen to suggestions and input from CommunicationFIRST, the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, and The Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint; and who ultimately did not remove the restraint scenes or add a warning about them at the beginning of the film, despite her promise to do so. Perhaps the reason why Sia was so unprepared for the backlash to this film, was because she completed it on the assumption that autistic people are incapable of advocating for ourselves or providing input on issues that affect us. This was her achilles heel, and it mired the project in ableism. But apparently, ableism was not enough for Sia. The list of racial offenses includes but is not limited to: white dancers and characters in Black hairstyles such as Bantu knots (Ziegler included- she wears box braids in two dance scenes); a Chinese immigrant abusing his wife and murdering his son (hate crimes against Asian Americans are surging right now and this scene certainly didn’t help with the stigma that the community is facing); a scene in which Ebo- who, may I remind you, is the only character with HIV- tells Zu that his autistic brother is dead and that the people in his village considered autism to be a curse; Zu’s drug dealer (who appears to be white?) with his hair in cornrows while wearing various appropriated Asian clothes; a scene where Zu refers to a clay figurine as her spirit animal (Zu is not Native American and neither is Kate Hudson); and yet another bizarre dance scene in which Zu is wearing what appears to be an Asian dress, Music has on a headdress and clothing with a collar reminiscent of a qipao, and Music’s grandmother has literal chopsticks in her hair. Yikes. (Music’s white grandmother with chopsticks in her hair, wearing an article of clothing that is ambiguously East Asian but that, to my knowledge, doesn't fall directly in line with any actual style of dress in any modern East Asian culture) (Kate Hudson as Zu, wearing a dress that appears to be East Asian in origin) (Maddie Ziegler as Music, wearing a headdress and a dress with a collar that resembles a qipao. A fuller image of Zu’s dress can be seen in the background as well) I wouldn’t have even noticed the chopsticks in the grandmother’s hair if it wasn’t for my girlfriend Abby (who has mixed Korean and Japanese heritage), who watched most of the film with me and pointed it out as the scene ended. It was hard to take in everything that was going wrong, particularly because this dance sequence happened directly after the horrifying murder scene where a Chinese man kills his son after choking his wife. I still can’t figure out why Sia felt the need to include that scene, particularly since it’s not at all relevant to the plot. Then again, most things in this movie don’t make any sense. It feels like Sia tried to squeeze in every single offensive stereotype and instance of cultural appropriation that she could find. It makes me wonder how there wasn’t any substantial pushback from POC members of the cast or production team. It's likely that there was, but their concerns were ignored. It wouldn’t be the first time a white director has ignored critique on issues of race. But it’s a shame, because tragically poor decisions lie around every corner in this film, to such a degree that Abby and I had no choice but to laugh hysterically at them. The common thread that ties everything in Music together is this: Sia is trying to tell stories that aren’t hers to tell. She attempted to tell stories about autism, about Africa, about HIV/AIDS, about immigrants, and about domestic violence. Every single one of those attempts ended up reinforcing existing negative stereotypes. The only storyline she has credibility to tell is the one about addiction, and that is the strongest element of the film overall. If she had simply stuck to making a film about drug abuse without drawing in all of these other disparate groups of people, it would have been so much better for everyone involved. There are many other critiques of this movie out there, many of them written by nonspeaking or minimally speaking autistic people, which you should go read in addition to this one. Hari Srinivasan and Niko Boskovic have both written powerful reviews, and CommunicationFIRST has released a short film called Listen that everyone should watch as well. There was no way for me to cover every aspect of what went wrong here, or every single way that the film is out of step with reality. Another brief example that comes to mind is a scene at the very end of the movie where a service dog for Music randomly arrives in the mail, which is…. not how partnering with a service dog works (to say the very least). So many tiny details like this warrant further discussion, but I am unable to unpack all of them right here. So I just hope that, after reading this and however many other reviews you’ve already encountered, you will not give Sia any of your money by renting or purchasing this film. There are much better places to spend your money, and you can start with the three organizations I mentioned earlier in this piece: CommunicationFIRST, the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, and The Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint. All of these organizations need donations to continue the vital work they are doing. If you’ve made it all the way to the end of this piece, I want to thank you for taking the time to listen to my voice as an autistic person and survivor of prone restraint. There are so many other people in the community, particularly nonspeakers, who everyone should also be actively learning from. Sia failed to listen, but you can counteract her ignorance with education and understanding. - Eden If you would like to support me financially as I go through college and continue work for this account, you can donate to me via my Venmo (@ Eden-Summerlin) or my PayPal, paypal.me/EdenSummerlin.

21 Comments

Someone suggested that I compile all of the essays I've written on Tumblr and put them all in one place as downloadable PDFs, so that's what I'm doing now. They're listed in alphabetical order by title, which is still tedious but hopefully not as tedious as it would be if they were just randomly plopped everywhere. These are all free, obviously, and you can print them out, cite them, send them to people, etc. But if you have the ability and you want to tip me/ provide me with some financial compensation (seeing as I'm going to be college student in the fall), my Venmo is @Eden-Summerlin and I would very much appreciate it.

What is ABA, and what are its roots?Is ABA backed up by scientific evidence? Is it ethical?Personal experiences with ABAThis is not an exhaustive list of resources, and there are many more I could include. I will probably add more to this post as time goes on. But for now, this is what I've gathered. If you are a current ABA therapist, the parent of a child going through ABA therapy, know that this is a space where you are encouraged to learn and grow. We know you have good intentions, and we encourage you to listen to autistic people to provide the best care you can for autistic children. If you are an autistic person who has experienced ABA yourself, know that we value you and appreciate your presence in the world.

If anyone has suggestions for articles or resources I should add, please comment on this post. - Eden The video is complete! Click the button below for the link to our YouTube channel, to watch the first-ever video compilation of responses sent in by our Instagram followers. The question asked was, "What is your favorite thing about being autistic? Why?"

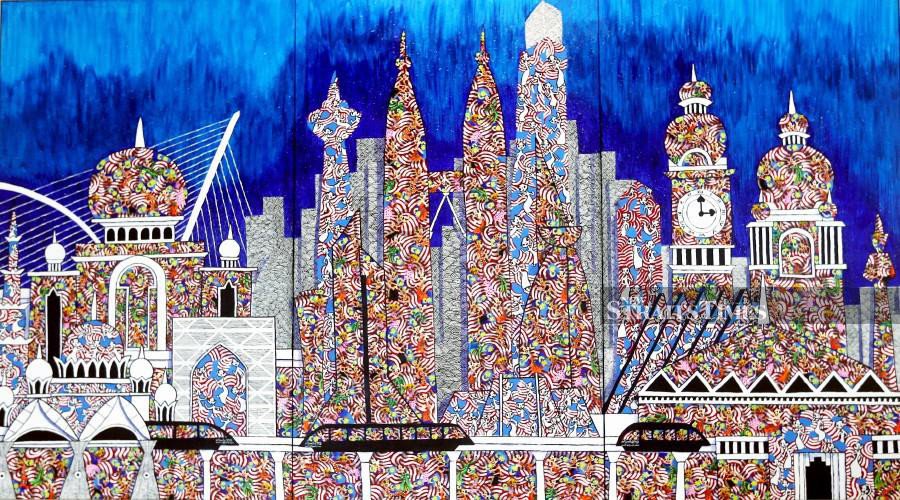

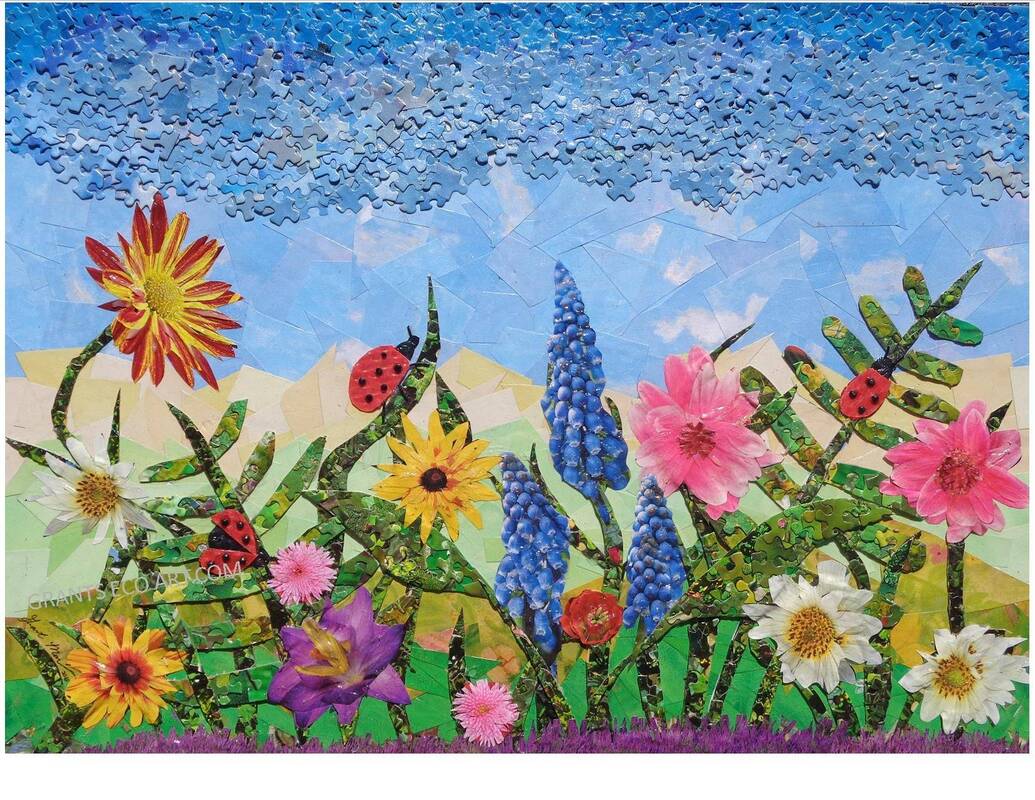

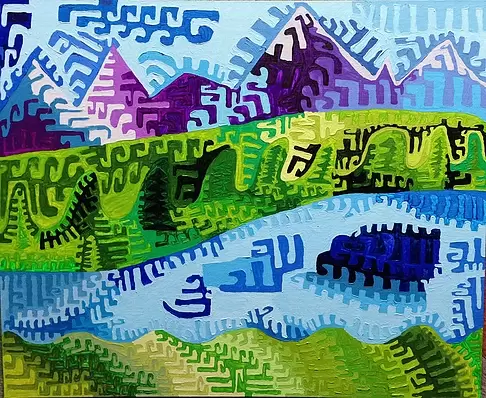

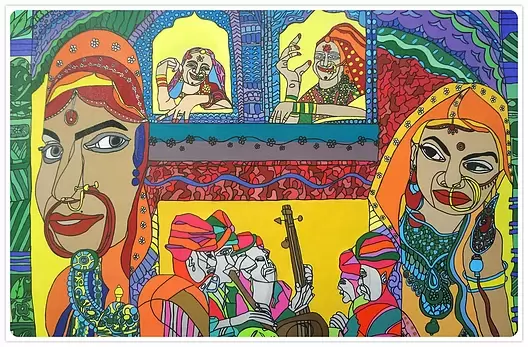

Eden typed out captions for the video (in English), to help those with auditory processing difficulties and those who are Deaf. You can activate the captions by clicking the CC button on the video. This is a masterpost of sorts, compiling a list of several modern-day autistic visual artists, links to their websites, and images of their art. One very good source for exploring autistic people's art is The Art Of Autism (https://the-art-of-autism.com/), a nonprofit dedicated to sharing the art and writing of autistic and neurodivergent artists. Here is a list of autistic artists to look into, in no particular order: Wan Jamila Wan Shaiful Bahri Wan Jamila is a teenage artist from Malaysia who was diagnosed with autism at the age of four, and finds verbal communication difficult. She creates intricate paintings that reflect how she views the world. Her website is http://artjamila.com/ Aiden Lee Aiden Lee is a teenage autistic artist with ADHD and anxiety from Canada, who could not speak until the age of four. He creates whimsical, colorful paintings that express his thoughts and emotions. His website is https://www.aidenlee.net/ Grant Maniér Grant Maniér is a young autistic "eco-artist" from the United States who uses recycled material like paper and puzzle pieces to create colorful works of art. His special interest in paper blossomed into this unique recycled art form. His website is https://www.grantsecoart.com/ Karissa Narukami Karissa Narukami is an autistic artist from Canada who has a topographic memory, meaning that she remembers the exact contours and structure of every environment, object, and person she sees. She uses ink and watercolor as her medium. Her exhibition website is https://theedgekarissanarukami.com/ Dana Anderson Dana Anderson is a nonspeaking autistic artist with Down Syndrome from the United States, who uses acrylic paint to create abstract works of art. She is nonspeaking and requires substantial support in everyday life, but is a highly intuitive and skilled abstract artist. Her website is https://www.danaandersonart.com/ Dominic Killiany Dominic Killiany is a minimally speaking autistic artist from the United States who uses acrylic paint to create works of art that play with symmetry, color, and line form. His most frequent subjects are animals and cityscapes. His website is https://www.dominicreations.com/ Tierney Bishop Tierney Bishop is an autistic mixed-media artist from the United Kingdom who uses acrylic paint and fused glass to create expressive works of art. She likes to paint landscapes, and to use bright colors. Her website is https://www.tierneytheartist.com/ Megan Rhiannon Megan Rhiannon is an autistic artist with aphantasia (the lack of ability to think visually) from the United Kingdom, who works digitally and in small sketchbooks. Her drawings are inspired from occurrences in everyday life, and she often draws on her experiences as an autistic person to create her pieces. Her website is https://www.megan-rhiannon.com/ Amrit Khurana Amrit Khurana is an autistic visual artist from India who is minimally verbal. She uses ink and paint to create intricate and expressive pieces that capture her observations of the people and environments around her. Her website is https://www.amritkhurana.com/ Niam Jain Niam Jain is an autistic, minimally verbal visual artist from Canada who creates colorful abstract paintings. His work has received the attention of many esteemed art critics, who believe that the sophistication of technique Niam exhibits is quite unusual for his age. His website is https://niamjain.com/ Grace Walker Goad Grace Walker Goad is a minimally verbal autistic artist from the United States who creates abstract paintings, due to her low muscle tone. She expresses a keen understanding of color and composition, which is readily apparent in her work. Her website is https://gracegoad.com/ Iris Grace Iris Grace is a young artist from the United Kingdom who was diagnosed with autism at the age of two, and is now learning to speak. She and her therapy cat, Thula, like to create abstract paintings with soothing colors. Iris Grace pays very close attention to detail, and has a firm grasp on line, color, and composition. Her website is https://irisgracepainting.com/ Moontain Moontain is an autistic artist from France who paints highly intricate abstracted paintings of animals, humans, plants, and environments. His paintings are spiritual in nature, and draw on his intuitive sense of line and form. His website is https://moontain.org/ Jimmy Reagan Jimmy Reagan is a minimally verbal autistic artist from the United States who uses acrylic paint to create abstracted pieces inspired by artists such as Pablo Picasso and Vincent Van Gogh. His favorite subjects are people and animals, so he likes to paint portraits. His website is https://www.throughjimmyseyes.com/

... Thus concludes this list of autistic visual artists. My next post will be a list of autistic musicians. If you liked this post and want me to do a part two, let me know by commenting on this post or by emailing us at [email protected] -Eden What Is Autism?

by Eden of @the.autisticats What is autism? Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition that affects every aspect of a person’s cognition, embodiment, and experience of the world. It is not a disease, and it is not a bad thing, it’s just a different neurotype. Autism alters a person’s sensory processing, social interaction, motor skills, emotional regulation, and many other things. It is caused largely by genetic factors, with at least 81% of autism likelihood being determined by genes (Pearson). The diagnostic criteria for autism includes: altered sensory processing, difficulty with social interaction, and restrictive and repetitive behaviors and interests. Autistic people process much more sensory information than neurotypical people (Remington, et al), so our experience of the world is sometimes confusing and chaotic. We observe details more acutely than other people, and sometimes have trouble generalizing concepts because of this heightened perception. Neurotypicals usually only use a couple of examples before generalizing, for example, being told that an orange cat and a black cat are both cats, then seeing a brown cat and knowing that it’s a cat (even though it’s not orange or black); whereas an autistic person might need more examples of different colored cats to understand that a brown cat is still a cat, because we notice and place more importance on the details of the animal (color, ear shape, etc.) than we do the gestalt (shape and general mannerisms of the animal). Because we perceive so much sensory and emotional information, we can often become overstimulated. In order to regulate our sensory and emotional processing, we do what’s called “stimming.” Stimming is short for self-stimulatory behavior, which is any repetitive motion or action that soothes us or provides us with the sensory input we need. Everyone stims, for example by twirling their hair or tapping their foot, but autistic people stim more often and more obviously, because we have so much more to regulate. Is autism a “male” condition? Autism is diagnosed more frequently in cis males than in women, trans & nonbinary people, with the estimated ratio of autistic cis males to cis females being 3:1. However, many professionals speculate that the ratio is actually 1:1, meaning that equal numbers of males and females are autistic. Women, trans & nonbinary people are currently and historically underdiagnosed, due to a difference in presentation and masking ability, as well as the fact that most diagnostic criteria is centered around the male-typical presentation of autistic traits (National Autistic Society). Additionally, recent research suggests that a substantial percentage of autistic people are gender-nonconforming, nonbinary or transgender, indicating that gender variance is more common in autistic people than in the general population (Strang, et. al). Do autistic people have empathy? The short answer is yes. There are two types of empathy, cognitive empathy and affective empathy (Wilkinson). Cognitive empathy is the ability to accurately predict how another person must be feeling based on context clues, whereas affective empathy is the ability to feel what someone else is feeling. Autistic people often have extreme affective empathy, and are very sensitive and responsive to people in obvious distress (Brewer). Cognitive empathy is sometimes a struggle for us, and it’s not because we don’t have the ability to think about how someone else might feel, it’s because we have trouble understanding how a neurotypical person would react to stimuli. We are often said to lack “Theory of Mind,” but really, we lack “Theory of Neurotypical Mind.” Our “Theory of Autistic Mind,” however, is intact. How many neurotypical people do you know, who can accurately understand and predict how an autistic person is feeling in a given situation, based on context and body language alone? Several studies have shown that neurotypical people are impaired in their ability to understand how autistic people are feeling and what they’re reacting to (Milton). It could be said, therefore, that neurotypicals lack Theory of Autistic Mind, as much as autistic people lack Theory of Neurotypical Mind. Should I say “person with autism,” or “autistic person”? Although many non-autistic people refer to us as “people with autism,” the vast majority of autistic people want to be called “autistic.” We like identity-first language, not person-first language. This is because autism is integral to who we are as people, and it shapes every aspect of our experiences and interactions with the world. Just like you wouldn't call a gay person a "person with gayness" or a black person a "person with blackness" you wouldn't call an autistic person a "person with autism." We know there's nothing wrong with being autistic, so there's no reason to distance ourselves from reality. Just because some neurotypicals use the word "autistic" as an insult doesn't mean we should concede and agree with them that being autistic is bad. Separating a person from their autism implies that there is something inherently wrong, bad, or sub-human about being autistic. Overly emphasizing the humanity of autistic people implies that our humanity is up for debate, and that autism would disqualify us from human status if it were viewed as a core part of our identity. It implies that there's a neurotypical person hiding "underneath" our autism. Calling someone a "person with autism" is like saying "I know you're autistic, but you're still a (neurotypical) person underneath." If you called a black person a "person with blackness" that would be like saying, "I know your skin is dark, but you're still a (white) person underneath." This makes the standard of humanity based on neurotypicality, whiteness, etc. This is why autistic people reject "person-first" language. It denies us humanity as autistic people. We aren't neurotypical, just as black people aren't white, and gay people aren't straight. That doesn't make us any less human. What are some areas autistic people excel in? Autistic people are extremely skilled at pattern recognition. We perceive small details and link them together, observing how they form complex systems of patterns. This ability to recognize patterns, and sort items or concepts into schema associated with those patterns, is called systemizing (Baron-Cohen et al; Smith; Chan; Khazan). We also have an enhanced perceptual capacity, meaning that we can perceive and process more information at once than neurotypicals can (Remington; Mottron et al). This is useful in situations where attention to multiple stimuli at once is required, and means that we notice more of the world around us than neurotypicals do. Our capacity to perceive is enhanced, and so is our perception itself. Autistic people are much more sensitive to sensory stimuli in general, and have been proven to have very acute visual and auditory perception (Bonnel; “Enhanced Motion Perception”; Mottron et al). Autistic people also have a heightened ability to discriminate between pitches, and are much more likely than the general population to have perfect pitch (Sarris; Stanutz; Bonnel). One other music related strength is that autistic people have an exceptional short and long term memory for melodies (Stanutz). Not only are we more perceptive than the general population, we’re more creative and original. In a study done on autistic people and neurotypicals who were told to think of novel uses for a paperclip and a brick, although the autistic people generated fewer responses, they came up with more original, creative ideas (Cohen). Autistic people also tend to be less prone to the effects of implicit social bias on the basis of race, gender, and other characteristics. While autistic people cognitively understand stereotypes, and often exhibit some implicit biases, the overall magnitude of those biases is reduced compared to those of neurotypicals (Birmingham). Works Cited “Autism and Gender.” National Autistic Society, National Autistic Society, 8 Aug. 2019, www.autism.org.uk/about/what-is/gender.aspx. Baron-Cohen, Simon et al. “Talent in autism: hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences vol. 364,1522 (2009): 1377-83. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0337 Birmingham, Elina, et al. “Implicit Social Biases in People With Autism.” Psychological Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4636978/. Bonnel, Anna, et al. “Enhanced Pitch Sensitivity in Individuals with Autism: A Signal Detection Analysis.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 15, no. 2, 2003, pp. 226–235., doi:10.1162/089892903321208169. Brewer, Rebecca. “People with Autism Can Read Emotions, Feel Empathy.” Scientific American, Scientific American, 13 July 2016, www.scientificamerican.com/article/people-with-autism-can-read-emotions-feel-empathy1/. Chan, Amanda. “Autistic Brain Excels at Recognizing Patterns.” LiveScience, Purch, 30 May 2013, www.livescience.com/35586-autism-brain-activity-regions-perception.html. Cohen, Barb. “Autism and Creativity.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 18 Dec. 2016, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mom-am-i-disabled/201612/autism-and-creativity. “Enhanced Motion Perception in Autism May Point to an Underlying Cause of the Disorder.” ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, 8 May 2013, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/05/130508131829.htm. Khazan, Olga. “Autism's Hidden Advantages.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 4 Oct. 2017, www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/09/autism-hidden-advantages/406180/. Milton, Damian E M. “Autism, Counselling Theory and The Double Empathy Problem.” Kent Academic Repository, University of Kent, 2018, kar.kent.ac.uk/67614/1/Autism%20DEP%20counselling.pdf. Mottron, Laurent, et al. “Enhanced Perceptual Functioning in Autism: An Update, and Eight Principles of Autistic Perception.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 36, no. 1, 2006, pp. 27–43., doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7. Pearson, Catherine. “Genetics By Far The Biggest Factor In Autism Risk, Study Says.” HuffPost, Huffington Post, 17 July 2019, www.huffpost.com/entry/autism-genetics-risk_l_5d2f51aee4b0a873f645a519. “People with Autism Possess Greater Ability to Process Information, Study Suggests.” ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, 22 Mar. 2012, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/03/120322100313.htm. Remington, Anna M., et al. “Lightening the Load: Perceptual Load Impairs Visual Detection in Typical Adults but Not in Autism.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 121, no. 2, 2012, pp. 544–551., doi:10.1037/a0027670. Sarris, Marina. “Perfect Pitch: Autism's Rare Gift.” Interactive Autism Network, Interactive Autism Network, 2 July 2015, www.iancommunity.org/ssc/perfect-pitch-autism-rare-gift. Smith, H. and Milne, E. (2009), Reduced change blindness suggests enhanced attention to detail in individuals with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50: 300-306. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01957.x Stanutz, Sandy, et al. “Pitch Discrimination and Melodic Memory in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Autism, vol. 18, no. 2, 2012, pp. 137–147., doi:10.1177/1362361312462905. Wilkinson, Lee. “Affective and Cognitive Empathy in Autism.” Best Practice Autism, 1 June 2019, www.bestpracticeautism.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-empathy-myth-in-autism.html. Strang, John F, et al. “Increased Gender Variance in Autism Spectrum Disorders and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24619651. There are certain common phrases, like "What's up?" or "How's it going?" that have no direct logical answers. As an autistic person, being asked either one of these two questions is usually quite stressful. See, I know how I'm supposed to respond to a simple "How are you?" or "How was your day?" There are straightforward responses to those questions, there are scripts. I could respond with "I'm good, and you?" or "It was fine, how was yours?" and they'd say "It was good," and we'd smile and walk away, or move on to more interesting conversation topics. But with questions like "What's up?" it's not logical or appropriate to respond "I'm good, and you?" because the response doesn't fit the question. The question is, "What is up?" And that, my friends, is a mystery.

When faced with a "What's up?" my go-to response as of late (and by that I mean for the majority of my life) has been "the ceiling," or "the sky," depending on the location of myself and the other person. Other times, I say something like "I'm standing in this line with you." These are humorous yet logical responses to a question that has no clearly defined answer, if the question is to be interpreted in a manner faithful to its intended meaning. From what I've observed of neurotypical conversation, the question "What's up?" invites a myriad of completely different responses, each valid in their own way. An answer could be the classic "Not much, what's up with you?" but a more sophisticated and honest answer might be "I just finished a math test," or "I'm headed to my sister's basketball game." The problem for me is, I don't know which response to use in any given circumstance, given that the responses to "What's up?" are usually specific to the respondent. Additionally, sometimes the question isn't intended as a question at all. Sometimes, it's intended as a greeting, and the person asking the question doesn't actually want a response. Even if the question is genuine, the person probably isn't super invested in hearing about your day, so you have to limit your reply to a short sentence with a return question. Not knowing which short sentence and return question to say, if any, is a problem exacerbated by the fact that I can't tell reliably when a person is asking the question genuinely, or as a greeting. So, to avoid incorrect or unwanted answers, I limit my replies to short and simple references to the sky, ceiling, or other aspect of our shared environment. I simply don't have the energy or willpower to figure out what it is that every "What's up?" -er wants from me in my response, so I don't give it to any of them. I get frustrated and confused whenever I'm asked a ridiculous question like "What's up?" And yes, it really is a ridiculous question. It's illogical and has no clear answers. Why neurotypicals have universally decided that it's a good conversation opener is beyond me. There are no rules, no scripts, no reasonable and clearly defined boundaries for what to do in a "What's up?" situation. Yet, literal answers to such a question are deemed "wrong" and socially unacceptable. People who answer "the sky" or "the ceiling" are frowned upon for not putting in the effort to maintain the facade of amicable social interaction that is so clearly beneficial to both parties and entirely necessary for the day to move forward. And that is precisely the reason why I continue to answer the way I do. I don't care about that facade. Sure, I'm perfectly happy to play along when there are rules, when I know that I'll be successful if I follow the script, and that perhaps my day will be slightly enriched by a smiling interaction with an acquaintance. But should that aquaintance decide to make my life exponentially more difficult by choosing to play a game with no rules, in which I could be penalized for an arbitrary reason that was never spelled out beforehand... in that case, I will simply refuse to play. I rely on scripts to get me through the day, and I have nothing to hold onto but concrete reality when an un-scriptable question or comment comes my way. My experience of life and social interaction is detailed and intense, and this constant feed of sensory, social, and emotional input is often chaotic and overwhelming. Without scripts, I have no navigation tools to row through the choppy waters of socialization that come with the five minutes before the bell rings at the end of class, or an informal greeting in a coffee shop. There's so much information to sort through at any given moment, so it would simply take too long for me to formulate a completely original response to every question people ask me, in the time frame allotted. If I don't remember my scripts, I end up simply failing to respond. I can't count the number of times someone has said something to me as they passed me in the hallway at school and I only registered what they said three seconds after walking past them. By that time, it's too late. So I have to be prepared with my "Good!" s and my "Fine, how are you?" s. But what happens if the person walking by, who I might not even recognize at first, asks me "What's up?" Chances are, I won't respond at all, and they won't even know I heard them- not for lack of trying, but because I simply can't. Neurotypicals and allistics: be clear and direct when communicating with autistic people; and if you're not going to be clear or direct, at least make sure we have adequate time to respond. I promise you, we're not being robotic or dull or emotionless because we want to come off that way. Our world is a lot more colorful and chaotic than yours, and we need your help to navigate it. So, please don't ask me "What's up?" Look above you and find out for yourself. -Eden As some of you might already know, due to posts on our instagram page, I'm currently enrolled at a college called Landmark.

Landmark College is a four year college located in the small town of Putney Vermont, within the United States. It is a small school (400-500 students) that specializes in teaching differently, offering programs and support for students with Autism, ADHD, Dyslexia, and other learning differences. It has been awarded Best Undergrad Teaching College of 2020 and Most Innovative College of 2020 by U.S News on September 9th of 2019. So far I've only been at Landmark for one semester and as someone who has always struggled with academics, never have I ever felt so confident in learning. I've learned so much about myself within the past almost three months! I have a great support system, a good circle of friends, and an awesome roommate. Usually within my first semester, especially during winter, I fall into a deep depression which is mainly because of seasonal depression but also due to stress from school. This year I haven't felt myself hit that low point yet. My grades are all A's and B's and my professors are wonderful. They really try their hardest to connect with each student to find out what works best for them and how to support them in any way. My psychology professor even brought in a box of fidget toys and coloring pages for my class to use during his lectures. Currently I've been very active with Landmarks LGBTQIA+ diversity center, Stonewall and I hope to get a job as a staff member for the center next semester. I've done a couple of open mics here and there and sometimes I'll just bring my guitar to the dining hall and just start playing because why not? The community here is so strong. Everyone supports each other regardless of their background and the transition from home-life to college-life was so smooth that I rarely feel homesick. If any of you are interested in learning more about Landmark, I've added the link to their website in the Useful Links section of the website. And if you have any questions, feel free to ask! -Leo Last night, I stumbled across this TED Talk given by an autistic artist and advocate, Dr. Dawn-Joy Leong. Her talk really resonated with me, and I found the immersive video and audio towards the end of the talk to be a wonderful representation of the joys of stimming and presence in sensory experience. Her speech was all-in-one: an explanation of what autism is, the current politics of autistic self-advocacy, and an open door into the world as viewed through autistic eyes. Anyway, enough of me gushing about it; you can watch it for yourself here.

- Eden The Picnic

by Eden of @the.autisticats It was a warm day in Illinois at the end of August, two weeks before Michelle was supposed to leave town for college. The day prior, she had texted me to ask if I wanted to have a picnic at Greenwood park, to see each other and say our goodbyes before she left. That sounds like fun! I’ll ask my mom, I replied. My mom was eager for me to get out of the house, so I let Michelle know I could come. A few hours later, she asked if it was okay for her best friend Natasha, and Natasha’s boyfriend, Brandon, to tag along. That’s fine, I said, ask them to bring some food as well. Michelle picked me up from my house in her red sedan the following afternoon. I carried an old blanket and a reusable grocery bag full of picnic food to the car, where I saw Natasha in the passenger seat. I sat in the back seat with Brandon, who looked like he’d been out in the sun, as Michelle pulled out of my driveway. I put my bag and blanket on the car floor and buckled in, then caught him eyeing my worn-out sneakers and baggy green sweatshirt. I eyed him back, noting the blue friendship bracelet on his left wrist, and wondering if that meant I should feel less intimidated. Natasha turned around in the passenger seat to look at me, tucking her dyed-blonde hair behind her ear as she smacked and chewed on a piece of mint gum. “So who are you, again?” “I’m Abbie.” She turned back towards Michelle, unsatisfied with my answer. “We go to school together,” said Michelle, keeping her eyes on the road. “Well, went to school together. School is over now,” I corrected her. “Mhmm…” Natasha sat back in her seat, then took out her phone to check her reflection. As she rearranged a few stray hairs and applied lipgloss, I noticed that she had a lifeguard whistle around her neck. She seemed like the lifeguard type. I sat quietly for a few more minutes, peering out the window at passing cars and fields, before realizing that I didn’t smell anything other than the Mexican food at my feet. “What food did y’all bring?” I asked. Silence. Then Michelle took pity on me. “There are some sandwiches in the trunk. I don’t know what else.” “Okay, that sounds good… I brought bean and cheese burritos, and some chips and guacamole. I made all of it this morning. I think y’all will especially like the guacamole. It’s my grandmother’s recipe. She passed away earlier this year, but my mom already knew how to make it, so we didn’t lose the recipe with her.” “Wow, that’s sad,” Natasha remarked without feeling. “Not really. Eating her recipes makes me feel close to her even though she’s gone. It’s like she becomes part of me, or something,” I laughed, “Maybe when you eat the burritos you’ll feel that way too.” “Um… I hope not,” said Natasha. I saw Michelle give Natasha a brief look. The kind of look that says, I know how you feel, but leave her alone. Or maybe, I’ve talked to you about this. I knew I must have said something wrong, I just didn’t know what. “Yeah maybe not, since she’s not your grandmother,” I tried to correct myself. None of them responded. I kept quiet the rest of the car ride. Michelle and I had been neighbors when we were kids. She lived across the street, and my parents encouraged me to play with her often, so we did. I’d go over to her house for after-school snacks and weekend playdates in elementary school. She liked to control the games we played, and that was fine with me because I wasn’t really sure how to play them anyway. We were close in elementary school, but less so in middle school, when she moved to the other side of town. In high school, she only acknowledged me when she knew none of her other friends were around. I was mostly okay with that. I took what I could get. We didn’t talk much at school, so the majority of our contact was over text. I initiated conversation most of the time, sending her memes I thought she might like. She usually responded with an LOL, or haha! Something like that. The last time she had invited me to do something was junior year, to come over to her house for a Halloween party. I was dressed head to toe like a phoenix, with a mask covering my face, so I’m not even sure anyone recognized me. That was my first party, and my last. The odor of alcohol and inescapable pounding of the speakers overwhelmed me, so I ended up hiding in Michelle’s bedroom closet. She found me there after everyone else had left, when she was looking for her bathrobe. Once she’d gotten over the shock of seeing a giant phoenix crouched beneath her clothing rack, she offered to drive me home. So I was surprised when she invited me to go on a picnic, but it would have been silly for me to decline, seeing as I hadn’t done anything social for the entirety of the summer. We parked in the gravel lot outside Greenwood park. There weren’t any other cars, which made sense because our town was small and mostly rural, and it was a Tuesday afternoon. The park itself was a large field overgrown with weeds and wildflowers, and it didn’t have a playground or anything. It was just a park. A piece of public land that people went to when they felt like being outside in nature, which wasn’t hard to do where I lived anyway. Maybe that’s why it was so neglected. People had other places they could go. Everyone unbuckled and got out of the car. I picked up my grey blanket and bag of burritos and stood outside the car door, waiting for Michelle to get the other food out of the trunk. She took out a white styrofoam cooler with a red handle, and nodded her head towards the park entrance. We passed through the old wooden fence posts that lined the front end of the field, and headed to a spot in the clearing. The park was surrounded on three sides by a dense forest, mostly of oak and birch trees. Michelle stopped walking at a spot around 15 yards from the forest, where we could still see the car. We all looked at each other, and I realized that I was the only one who had brought a blanket, so I laid it down for all of us and took a seat. It wasn’t terribly big, but it would have to do. Michelle sat down across from me, then Natasha and Brandon on either side. The two of them sat as close to Michelle and as far off the blanket as possible. I was used to that sort of thing. Michelle and Natasha started chatting about college, and I learned that they’d be going to the same school, in Santa Cruz. Then Natasha turned to me. “What about you, where are you going to college?” “Oh, um… I’m- I’m not going yet. I’m taking a gap year,” I said. “Why?” She frowned. “Because… well, I’m just not ready yet. I’m working on regular life stuff first.” “Oh. Got it.” She smiled, but her eyes were cold. I got four burritos out of my bag, one for each of us, and unwrapped the tinfoil on one of them. I started to eat. Michelle saw me, then took out some sandwiches from the cooler. She passed one to Natasha, who passed it to Brandon and took one for herself. “Does anyone want a burrito?” I asked. No response. Then Michelle. “Maybe later, after my sandwich.” Natasha and Michelle talked about things best friends talk about, and how excited they were for California. Brandon chimed in occasionally, and I learned that he was already in college, in Arizona. He’d flown back to Illinois for summer break, to see Natasha and his family. I finished my burrito, and took out the chips and guacamole. I’d put the chips in a Ziploc bag and the guacamole in a tupperware, both of which I opened and placed in front of me on the blanket. There was a lull in the friends’ conversation, so Brandon took out his phone and a bluetooth speaker. “You guys down for some music?” “Yeah, totally,” said Natasha. Michelle nodded agreeably, and I said nothing. He started playing his music, placing the speaker on the center of the blanket, near my guacamole and chips. It was mostly rap, with a few of the year’s hit songs mixed in occasionally. I didn’t mind the music itself, but it was too loud for me to enjoy it. I sat through the first song, then a few more, but the drums and bass were really starting to bother me. Each thump and sharp edge of the snare drums hit me as a violent crashing wave, but the three friends seemed fine. Their conversation had resumed, gotten louder to compensate for the noise. I watched them as their voices distorted. Sound ate its way into my skull and my muscles tightened in response, as if that would keep it from pouring in. I needed the music turned down, or I would have to walk away. And I didn’t want to walk away. “Brandon, could you please turn down the music?” No response. I made brief eye contact with Michelle, but the friends continued to talk. “Brandon, could you please turn down the music?” I asked, louder this time. “Why?” Brandon turned to look at me. “Because it’s too loud,” I said, flinching. “This is too loud?” He repeated, picking up the speaker and thrusting it closer. The sound surged over my head and I began to drown in it. “Yes! It’s too loud!” I shouted, scrambling off the blanket. I must have kicked my guacamole when I tried to escape the speaker, because the next thing I knew, it was upside down on Natasha’s white jean skirt. She stared at me, eyes wide open. Brandon dropped the speaker. “What the fuck?!” Natasha yelled, “What are you, a spaz? Are you retarded?” “I’m sorry! I’m sorry!” Michelle looked frozen, and I wished I was too. Prickly heat built in my face and chest, the rattle of snare drums in the speaker piercing my ears and making me dizzy. I needed to make that sound go away. Turn the music down. Please could you turn down the music. Please turn the music down. Please, Brandon, turn down the music. A sob escaped as I reached onto the blanket, picked up the speaker, then threw it as far as I could. Brandon yelled, and ran after it. I couldn’t see very well anymore. Everything was blurry because of the tears. I barely made out a red-faced Natasha putting her lifeguard whistle up to her mouth. “Was that too loud for you? What about this?” Her voice echoed. Then she was on top of me, in the grass, blowing her whistle in my face. I heard Michelle yelling for her to stop, but it might have been my voice instead. The ringing and the pain kept coming and then Brandon was above me too, and I was hot and sweaty in my stupid green sweatshirt in the August sun, and my tears and mucus were hot as well. Brandon put his left hand on my shoulder and pushed me harder against the ground. “Why would you do that!? You broke it!” He roared. I tried to push him off but he was too strong, so I leaned over and bit his forearm, tearing off the blue friendship bracelet, then spitting it out. He howled in anger and pain as he recoiled, and I howled back. Natasha’s palm struck my cheek so I grabbed her arm, yanking her closer and then scratching her as she tried to pull away. Michelle must have yelled something severe at them, because they backed off slightly. I rolled onto my stomach, pulled myself off the ground, then sprinted towards the woods. They shouted after me. I didn’t stop running until my legs gave out and I collapsed on the forest floor, spiderwebs in my mouth and on my hands. Birds sang and squirrels hopped through the branches above me like the world wasn’t falling apart, but it was. I sobbed, picked up a stick and stabbed it into the soil, twisted it around and bent it until it broke. Memories flashed and swarmed, on rewind and replay. I was four years old, when I asked two girls in my pre-k class if I could sit with them during lunch. They said no, and I asked why. “Because you’re weird,” one of them said. I grabbed a handful of leaves off a nearby shrub and tore them all to pieces. I was eight years old when I was diagnosed with autism. The psychologist told my parents I was lucky, that I was “very high functioning”. I pulled myself up against a birch tree, shaking, and wondered what he would say if he could see me now. I was six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven years old when my parents pinned my arms to my sides as I cried, rolled me inside my favorite blanket and sat on top of me as I struggled for air, gasping, “I can’t breathe!” My mom was Natasha, my dad was Brandon, and I couldn’t escape them. Turn down the music. “Is this too loud?” Spaz. Retarded. I screamed, the power of my voice ripping my chest apart and sending tremors down my torso, tremors that kept coming as I lay there, sobbing in the dirt. I thought I might be trapped forever in that whirlwind of time and memory, but the forest was quiet and peaceful, and it slowly eased my body. I leaned into the birch tree and took some deep, shaky breaths. A chipmunk scurried in front of my sneakers, carrying an acorn in its mouth. It stopped for a moment and peered at me curiously, before scampering off. I wiped the tears from my face, and began to trace my fingers along the roots of the tree, touching each bump on its rough grey skin and letting my fingers dissolve into it. As I caressed the roots, I watched a procession of ants take small bits of leaves and tiny seeds back to their anthill. Some ants did not walk in line with the others. One of the stragglers was carrying a particularly large seed on its back, in a meandering path towards the same destination. I pondered the existence of the wayward ant, and hoped it would make it back to the nest. I sighed in exhaustion. There was a blanket of moss several feet to my left, which I pressed my hand into before lying down and resting my head on it. I turned my face so I could see the glow of sunlight around each soft green tendril. My fingertips grazed the edges of the moss, and I watched carefully as the little leaves bent down, then bounced back. A shiny blue beetle crawled up my arm from the moss, waddling slightly as it walked. I smiled, picked the beetle up, put it on my forehead, and looked up at the branches of trees. Each tree trunk diverged into branches, which expanded into fractals; imperfect tributaries of translucent flesh and solid bone. The bones swayed and bent at the whimsy of clambering animals, as the flesh shimmered in the wind. I let myself sink deeper into the soil, and breathed. I wasn’t sure how I was going to find my way back to the park, because I didn’t know where I was. I wondered briefly if I would be lost forever, but I thought that was unlikely. I knew I could follow the sun, which was a sort of relief, but it didn’t really matter. I was in no hurry to leave the forest. If Michelle cared enough to find me, she would. If she didn’t, I was happy to let the other animals care for me instead. |

AuthorsWe're the Autisticats: Eden, Leo, Laurel, and Abby. This is where we post our writing, musings about life, and other things we're working on. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed